Sensory Anxiety: Not Your Ordinary Anxiety

by Kelly Dillon

Let's talk about something that nearly every single person with sensory issues has to deal with: ANXIETY. Gosh! Even the word itself sets me on edge.

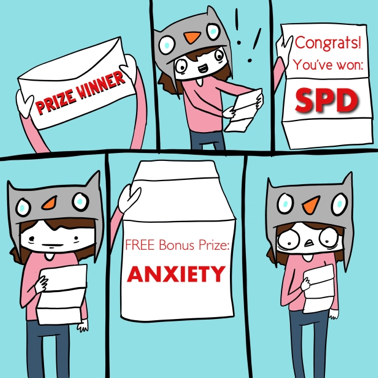

For people with Sensory Processing Disorder (SPD), anxiety comes as part of the package. It's the bonus prize that nobody wants.

SPD and Anxiety work together to cause mayhem. They play off each other, and create a spiral effect of symptoms.

Strangely, when we talk about sensory problems, anxiety is rarely part of that conversation. The focus is always on the sensory part of SPD. But I would like to shed some light on the chaos that anxiety can cause when it's teamed up with SPD, and why it's different than non-sensory anxiety.

But first, it's time for a little story; a short tale of my own experience with sensory anxiety to set the stage. The following is the true and slightly uncomfortable reality of my life:

I've always been told that the best - and perhaps only - way to conquer anxiety is to put myself into situations that make me anxious, and to push through it.(Whatever that means.)

I've done this for years.

I've done this most recently through college, where every morning before my commute to school, I had to give myself extra time because of anxiety-induced diarrhea and nausea. My agonizing stomach cramps and bathroom visit occurred daily, without fail. (I told you this was going to be an uncomfortable story.) I couldn't stomach food for hours…but, only on the days when I had school. There are no such things as coincidences in this magical sensory life.

Once I made it to school, I often had to give myself even more time to find a bathroom and change my shirt, which would've been soaked in sweat before my first class even began. I spent the large part of my day feeling enormously dizzy. My face hurt from a clenched jaw and the muscles in my back were sore from tension.

Often, I bought myself a warm drink in an attempt to soothe my trembling body, which was trembling on account of being both anxious and also cold. (Fact: when the body is anxious, blood rushes to the main organs, leaving the extremities feeling cold and/or numb.)

I'd come home at the end of the day and nap for an unreasonable amount of time, like 6 hours. My body was depleted, from what I assumed was sensory overload. One day it occurred to me that I was not only physically and emotionally exhausted from SPD, but also from my anxiety that was caused by my SPD. Then the anxiety and SPD and feeling helpless and feeling hopeless made me seriously depressed. Would the fun ever end? I wondered.

I went to college for four and a half years. I pushed through my debilitating anxiety every day, and wouldn't you know it, the last day of college rolled along, and that morning I had diarrhea and a sweat-soaked shirt. Just like the first day.

I went to college for four and a half years. I pushed through my debilitating anxiety every day, and wouldn't you know it, the last day of college rolled along, and that morning I had diarrhea and a sweat-soaked shirt. Just like the first day.The End!

I know, I know. It was a truly riveting tale. One that will certainly go down in history as one of the greatest stories known to man. But let's get back to what matters here. Physical symptoms of anxiety are only one part of the equation.

At the end of the day, I learned that pushing through my anxiety did nothing to help alleviate it. All it did was make me miserable and feel like I was weak for not being able to get rid of my symptoms.

Since that time, I've come to realize that the reason traditional methods of alleviating anxiety were not working for me was because I had a very good reason to be anxious.

Now it's time to introduce the second part of this equation: Sensory Processing Disorder.

In my case, my SPD has gifted me with overwhelming sensory sensitivity and the inability to function when having to process multiple sensory stimuli. In most environments, like a classroom for example, my body picks up on the sounds, smells, textures, and even the vibe in the air to an outrageous extent. My sensory brain is turned up to the highest setting and it isn't very good at turning off.

As one can imagine, having SPD is not fun. Anybody who says it is, well, they are a goober. It's called a disorder for a reason. It's not called Sensory Processing Fun Times All Around (SPFTAA). Although, I admit that would be a cool thing.

As one can imagine, having SPD is not fun. Anybody who says it is, well, they are a goober. It's called a disorder for a reason. It's not called Sensory Processing Fun Times All Around (SPFTAA). Although, I admit that would be a cool thing.Dear reader who I love so very much even though I've never met you,

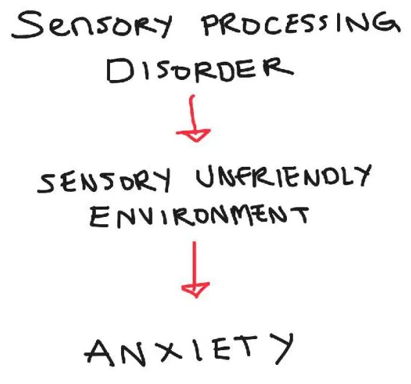

If you can relate to my gastrointestinal distress in sensory-ugly environments, please take comfort in the fact that what you are feeling both physically and emotionally is very normal. For instance, when the sound of most people’s voices is loud to the point of severe discomfort, being in a place with lots of people talking is going to give you anxiety. It makes sense.Let's briefly recap and take a look at the complete equation. Keep in mind, I spent a lot of time making this:

Consider this:

You wouldn't say to someone, "hey, I know there's a hungry shark in this swimming pool, and every time you've gone in he's bitten you, BUT you don't need to be anxious about swimming because if you keep going in, he won't bite you anymore!"

Yet, we've been telling ourselves, "hey self, I know you have SPD, and every time you go into a sensory unfriendly environment it's super distressing, but you don't need to be anxious this time because if you keep pushing through it, you won't have anxiety anymore!"

This concept of pushing through anxiety often works for regular, non-sensory anxiety. Allow me to demonstrate:

This concept of pushing through anxiety often works for regular, non-sensory anxiety. Allow me to demonstrate:When you were five you went to a birthday party. A person waved a bunch of balloons around your face and you FREAKED OUT. Fast forward ten years later, and you have anxiety whenever you see balloons.

To alleviate this kind of anxiety, you start to spend time around balloons. Maybe you go into a room where someone has placed a balloon. Maybe next time, you move a bit closer to it. After that, you touch one. Your balloon-related anxiety slowly improves over time. You are able to push through the anxiety by addressing the irrational thoughts and fears you experience, and replacing them with rational ones. "Balloons aren't scary. I do not need to feel anxious around them. I am ok."

**I'd like to note that when I say regular anxiety I do not mean less anxiety. Anxiety from having a neurological condition like SPD is a different kind of anxiety, not more or less severe than anxiety from other things.**

Now let me demonstrate how this concept does not work for sensory anxiety:

When you were six you went to a birthday party. You are sound sensitive, and during the party, kids were popping balloons. It upset you deeply. Fast forward ten years later, and you have anxiety whenever you see balloons.To alleviate this kind of anxiety, being around balloons will not reduce your anxious feelings because you are still sound sensitive, and balloons could potentially pop at any time. If they pop, it will scare you the same every time.

WHY DOES THIS HAPPEN?

The reason people with sensory problems have recurring, stubborn anxiety is because many SPD'ers lack the ability to habituate(become accustomed to) new information. Our unique sensory systems do not do well with what I refer to as POTENTIAL stimuli. We like routine and predictability. But a lot of sensory stimuli are neither of those things. The world is full of random, unusual and unpredictable things. When you have a brain that struggles to make sense of the predictable - let alone the unpredictable - it's easy to understand why anxiety is the result.WHAT DOES SENSORY ANXIETY FEEL LIKE?

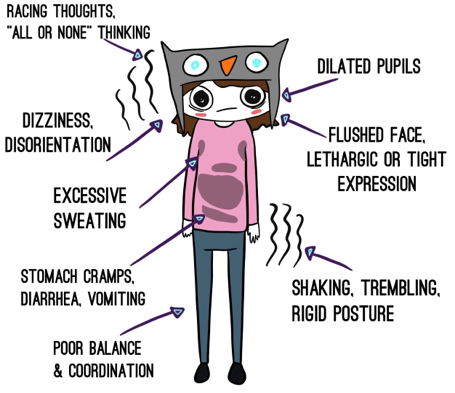

When you have anxiety from sensory issues, it presents itself the same way non-sensory anxiety does; the symptoms are virtually the same. It can be hard to distinguish between sensory overload and anxiety. Most commonly, SPD anxiety can look like this: However, if you notice, the symptoms of sensory anxiety are similar to symptoms of a freeze response. Unless the sensory stimulation or the anxiety reaches a breaking point, people with SPD tend to literally freeze during an anxiety crisis. The meltdown and shutdown occurs after, when they are in a safer space to let it all out. Of course, this doesn't always happen so nicely, and sometimes you find yourself completely dissociated and about to vomit from a fire drill in the middle of the hallway at school. It's equal parts inconvenient andembarrassing!

However, if you notice, the symptoms of sensory anxiety are similar to symptoms of a freeze response. Unless the sensory stimulation or the anxiety reaches a breaking point, people with SPD tend to literally freeze during an anxiety crisis. The meltdown and shutdown occurs after, when they are in a safer space to let it all out. Of course, this doesn't always happen so nicely, and sometimes you find yourself completely dissociated and about to vomit from a fire drill in the middle of the hallway at school. It's equal parts inconvenient andembarrassing!HOW DO I HANDLE SENSORY ANXIETY?

Consider the source! To fix or improve sensory anxiety, you have to learn what sensory-related problems give you anxiety in the first place. You don't want to keeping jumping into the swimming pool with the shark. Remove that shark before you go swimming!Here are some of my favorite, tried-and-true methods for relieving anxiety when it's tied to sensory issues:

With all that in mind, I must conclude with this: experiencing anxiety from having sensory issues is normal, common, and expected. Don't beat yourself up about it. Your brain is reacting as any brain would under the circumstances. I know some days the anxiety can be crippling. Other days, it can seem like it's on a permanent vacation! Flip-flopping like that can be draining and confusing.

Pushing through sensory anxiety won't work to alleviate it, but that doesn't mean you should stop pushing the boundaries of your life as a person with sensory issues. You don't have to go in the shark pool, but it's probably to your advantage to go up the edge and take a peek.

Kelly Dillon is an adult with Sensory Processing Disorder, and the writer and illustrator of the blog Eating Off Plastic, where she humorously chronicles her life with SPD. She is a proud SPD advocate for children, teens, and adults. Kelly enjoys

Kelly Dillon is an adult with Sensory Processing Disorder, and the writer and illustrator of the blog Eating Off Plastic, where she humorously chronicles her life with SPD. She is a proud SPD advocate for children, teens, and adults. Kelly enjoys

As a caveat: I don’t think sensory processing disorder is all bad - it also opens up worlds. Below on autistic perception from my book Always More Than One (Duke UP 2013).

ReplyDeleteBut first, let me repeat: autistic perception is a tendency in perception on a continuum with all perception, not a definition of autism. It is a style that has been remarked upon by the many autistics whose voices we've heard

throughout, a perceptual style that actively thinks-feels the edgings and contourings of fields of relation coagulating into instances of shaped experience.

As the writings of these autistics attest to, the direct experience of the in-actness of worlding results in an ecological sensibility to life-living. Lest it has not been clear enough when the concept has come up throughout

this book, let me repeat: while all autistics I have encountered prize this mode of perception, none of them would ever create a simplified relay between autistic perception and the everyday experience of an autistic. For

autism is a complex world at once full of perceptual richness and replete with painful misalignments to everyday neurotypical existence, many of them of the motor variety that make independent living if not impossible,

then very difficult.11 Not only that: there is no one single autism. Autism is a spectrum, with as many infinities of perceptual difference as there are within the misidentified "neurotypical" group.

What makes autistic perception so valuable for the rethinking of experience is the process of shaping, or the complexity of what Anne Corwin calls "chunking." Anne Corwin writes: "I often tend to sit on floors and other surfaces even if furniture is available, because it's a lot easier to identify 'flat surface a person can sit on' than it is to sort the environment into chunks like 'couch,' 'chair,' 'floor,' and 'coffee table."' 12 All perception involves

chunking, but what autistics have access to that is usually backgrounded for neurotypicals is the direct experience of the relational field's morphing into objects and subjects. Experientially speaking, there is never- for anyone - the direct apprehension of an object or a subject. What we perceive is always first a relational field. It is a key contribution of Whitehead to have created a whole philosophical vocabulary of process to make this clear.

Still, given the quickness of the morphing from the relational field into the objects and subjects of our perceptions, many of us neurotypicals feel as though the world is "pre-chunked" into species, into bodies and individuals. This is the shortcoming, as autistics might say, of neurotypical perception (that we are simply too quick to chunk) , and it is certainly one of the things that makes many autistics feel lost in a world overtaken by normopaths.

The foregrounding of the world in its morphability as experienced in autistic perception opens experience to a level of relation with the world which is rare. This level of relation is an ecological attunement to the multiplicity

that is life-living, for it attends, always, to the dynamic details of a process: autistic perception never begins with the general attribute, never assumes integration over complexity. It prehends, always, from the middle,

with an active regard for the emergent field's environmentality. In the register of autistic perception, the world is experienced as an ecology of practices. This results in a mode of existence that moves not from self to self, or

self to other, but from dynamic constellation to dynamic constellation. As Mukhopadhyay writes: "Maybe I do not have to try very hard to be the wind or a rain cloud. There is a big sense of extreme connection I feel with a stone

or perhaps with a pen on a tabletop or a tree . . . . There is no separation" (Mukhopadhyay and Savarese 2010). Cloud-like. Rock-like.